The recent CIJA sting on Paul McKeigue revealed a serious lapse of judgement on his part. But what it reveals from the perspective of international justice is immeasurably more significant: a rift between CIJA and the international legal community it aims to provide prosecution briefs for; affinities between CIJA and the White Helmets which raise wider concerns about Western-backed operations in Syria; and our neglect of the most egregious war crime in Syria.

Introduction

CIJA (the Commission for International Justice and Accountability) is a private initiative that gathers documentary evidence and testimony relating to war crimes in Syria. Readers may have seen articles and documentaries celebrating the organisation’s activities.[1]

Gathering robust evidence of war crimes is vital if their perpetrators are to be brought to trial. Holding perpetrators to account is part of a process of ensuring justice is seen to be done for the victims and survivors of those crimes, and it is also intended to alert prospective war criminals that they will have no impunity. Indeed, a core point of war crimes prosecutions is to signal, and seek to ensure, that what has happened will never happen again.

That strong intended prohibition is embodied in the Nuremberg Principles as the most fundamental crime punishable under international law. This, the Crime Against Peace, is committed in the ‘planning, preparation, initiation or waging of a war of aggression’ or ‘participation in a common plan or conspiracy for other accomplishment’ of any such acts. For without the occasion for them provided by a war, there would be no war crimes.

These thoughts frame the bigger picture that is to be drawn out in the following reflections on the strange story alluded to in this article’s title.

The CIJA sting was initiated after Paul McKeigue had sent some questions to CIJA’s director about his financial and business dealings. (These are appended to his statement on the sting.) They formed part of wider ongoing investigations into the destination and use of UK FCO funds disbursed for UK operations in Syria, also including Mayday. Someone from CIJA, adopting a fake identity, engaged McKeigue in a lengthy email exchange designed to find out, they have said, what else he knew about the highly secretive organisation. (The results of his inquiry have since been published on the website of the Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media.)

Readers interested in CIJA’s perspective on the story can find it covered by BBC, Guardian, Daily Mail and Times (paywalled); while more critical reflections are offered by Grayzone. My own view, as a fellow member of the Working Group, is that McKeigue’s admitted misjudgements illustrate the need for a collaborative approach to doing epistemic diligence on communications about controversial matters. But the concerns to which CIJA’s activities give rise are immeasurably more significant.

A rift between CIJA and international lawyers

In a previous article on the importance of assuring the integrity and probity of those involved in gathering evidence for prosecutions of war crimes, it seems I underestimated the extent to which lawyers involved in international criminal law and international humanitarian law already share the concerns alluded to there.

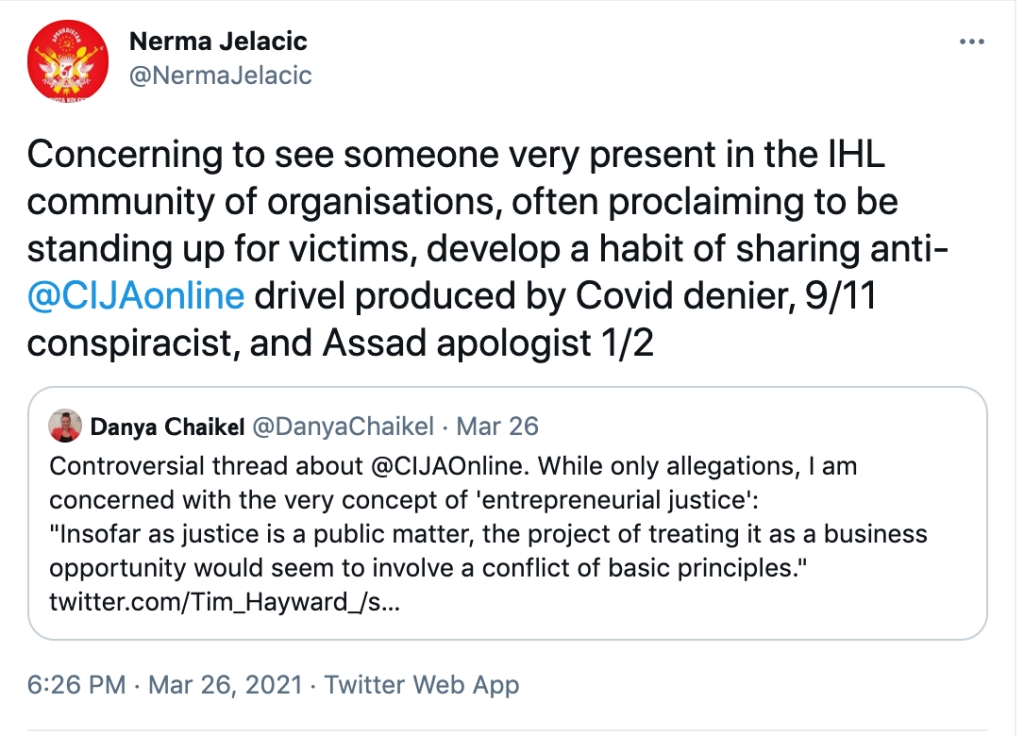

Certainly, misgivings about the CIJA model of ‘entrepreneurial justice’ amongst international lawyers – including some who are directly involved in seeking justice for the people of Syria – came to public attention in discussions of the CIJA sting on Twitter. One initial comment came from Danya Chaikel, an international lawyer who has worked for 15 years across several international criminal courts, tribunals, NGOs, professional bodies and the UN.

Chaikel pointed up a concern with the very concept of ‘entrepreneurial justice’ that was emphasised in my previous article:

“Insofar as justice is a public matter, the project of treating it as a business opportunity would seem to involve a conflict of basic principles.”’

This prompted a reaction from CIJA’s Director of External Relations, Nerma Jelacic.

Jelacic rebuked the respected lawyer for sharing ‘drivel’ from an ‘Assad apologist’ (to repeat only the most salient of her defamatory descriptions of myself) who belongs to the same Working Group as McKeigue. She concluded a thread on her theme by saying to Danya Chaikel:

‘Welcome to the category of a useful idiot in the Syria disinformation campaign.’

Chaikel, who said she had not even heard of the Working Group, was understandably disconcerted. (She is also unlikely, I imagine, to have personally encountered the kind of defamatory language that has routinely been used in smearing its members over these three years since the alleged chemical attack in Douma.) She responded that she herself had concerns ‘based on personal experiences & the questions I have about CIJA’s model & working methods.’

She added: ‘I receive a lot of pushback if I even ask questions, which is worrying.’

This point was echoed by Sareta Ashraph, another respected international lawyer whose impressive career to date includes serving on the UN Commission of Inquiry on Syria and on the start-up team of the International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism (IIIM). Ashraph confirmed that Chaikel ‘is expressing pretty common concerns about CIJA’s model. The “either you’re with us or against us” defensiveness continues to be a disturbing facet of CIJA’s response to concerns.’

This was too much for Jelacic: ‘I am shocked that a lawyer of Danya’s standing would promote Grayzone and Working Group and disgusted that you try to spin it’.

Initially Ashraph tries to urge Jelacic to step back a little so they might find a more conciliatory mode of engagement. She merely wants ‘to emphasise that no one should feel intimidated to raise concerns in the public sphere or be pushed into silence due to personal attacks.’ But the CIJA Director of External Relations appears implacable, even accusing the lawyer of being involved in a disinformation campaign. When Ashraph points out this is defamatory, Jelacic retorts:

‘No no no @SaretaAshraph it is you and Danya that got the likes from Hayward, Robinson, Miller, Blumenthal, Maté et al. I had nothing to do with that. You defamed yourself.’

Thus the spokesperson for an organisation responsible for gathering evidence for the most serious of crimes accuses an international lawyer of contributing to a disinformation campaign on the grounds that certain people have pressed the “like” button on Twitter. The bizarreness of this aside, such a serious accusation is ‘truly horrifying’, says Ashraph. Yet Jelacic persists, tweeting “we have the proof” and “let’s leave it at that until further details of your contribution to the Syria disinformation campaign are made public”. This protracted exchange ends with a final warning of legal action.

Among the things illustrated by all this is just how easily and carelessly people can get smeared as spreading disinformation: if it can happen to prestigious lawyers who specialise in the very field CIJA seeks to supply briefs for, it can happen to anyone.

But why such extraordinary defensiveness on the part of the CIJA spokesperson? Jelacic articulates this concern:

‘Danya’s tweets are very much used by the Working Group and Greyzone as proof that CIJA’s evidence is tainted and controversial, just like that of OPCW and White Helmets.’

Something interesting here is the implication of relevant similarities between CIJA, the White Helmets and OPCW with regard to the integrity of evidence to be used in war crimes prosecutions (which, incidentally, is not something the Working Group, Grayzone or even individual lawyers get to pronounce on).

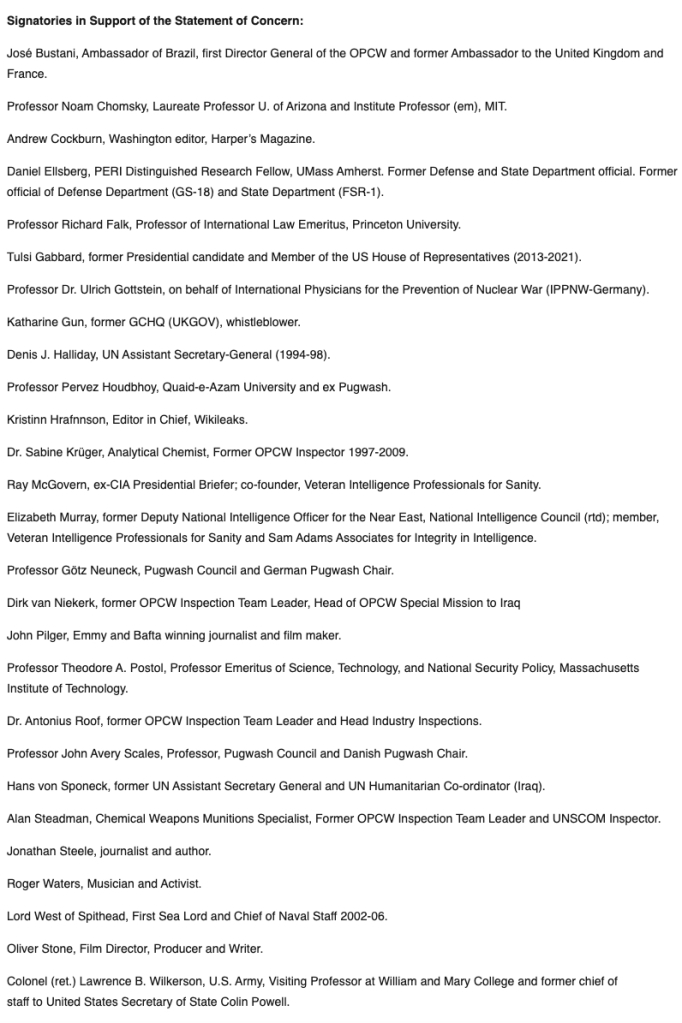

One might wonder why CIJA would want to peg its reputation to those other organisations rather than simply stand by the independent reliability of its own evidence. For the Working group has indeed raised concerns about the OPCW, specifically regarding its published report on the alleged 2018 chemical attack in Douma. These are shared by 5 former senior OPCW officials, including the founding Director General, and a number of distinguished public figures who have recently signed this Statement of Concern. Evidence and testimony that was used to support the conclusion of the contested report is understood to have been supplied by White Helmets. More generally, questions about the chain of custody of evidence and reliability of testimony in other cases have focused on the White Helmets’ role. Whatever one’s view on these matters, there are enough questions on record to warrant some caution about citing what White Helmets produce as a benchmark of evidence that can satisfy the burden of proof required in a criminal trial.

So how might the Working Group’s scepticism about the quality of the White Helmets’ evidence or OPCW’s final Douma report have any particular bearing on evaluations of the quality of CIJA’s work? Is it that they are in some way mutually supporting rather than independent?

How is CIJA’s reputation linked to that of the White Helmets?

The question of a connection between White Helmets and CIJA has not arisen purely from a heated Twitter exchange. It was implied by the BBC when featuring CIJA’s investigations in the opening of the first extra episode of the Mayday podcasts; and a second extra episode is trailed as being about the CIJA sting. (Mayday’s producer, Chloe Hadjimatheou, was the first to be alerted to the story by CIJA, as Working Group members know from her emails to them.) But what is the connection?

Conceivably, the White Helmets might have played some part in gathering CIJA’s witness testimony, in which case it would be a very significant one, but I do not know whether this is so.

An observable connection is that both the White Helmets and CIJA have figured prominently in publicity – articles, news items and documentaries – which all reinforce the message that Syria’s president is a uniquely culpable war criminal whose regime is beyond reform and should be supplanted in the interests of the Syrian people. Of course, this commonality would be unremarkable if one presumes it to be the reiteration of an indisputable truth about the situation. Yet whatever is true, the purpose of CIJA’s work is to provide proof of it, not presume it. And its stated mission is to gather evidence of war crimes committed on all sides. So there remains the question why CIJA’s stance regarding the quality of White Helmets evidence is not more detached.

A deeper aspect of the observable connection is that the publicity role played by both organisations is not a matter of simple chance. In the case of the White Helmets, as was noted by the Working Group in early 2018, and by others before that, the strategic objectives of their funders ‘provide strong prima facie grounds for considering the White Helmets as part of a US/UK information operation designed to underpin regime change in Syria’. UK government documentation refers to the ‘invaluable reporting and advocacy role’ played by the White Helmets. In the case of CIJA, none of whose promised cases against high-ranking Syrian officials has so far been brought to a court, the nature of their work and the promises made for it are familiar in the public mind. CIJA’s lack of impact hitherto in the law courts has arguably been offset by success in the court of public opinion. The image of its indefatiguable evidence gatherers has helped keep alive the indelible reputation of Assad’s government as being uniquely responsible for war crimes in Syria with the promise that hard evidence sufficient for conviction is in course of preparation. (CIJA has given an appearance of impartiality by also pursuing ISIS, but it has not investigated the Free Syrian Army or the other main opposition groups.)

To understand connections between CIJA and White Helmets, it is helpful to note that the creation of both was instigated by one man.

Alistair Harris, when invited to describe himself by Chloe Hadjimatheou in episode 2 of her Mayday podcast series, opts for ‘former UK diplomat’ and the two (needlessly) clarify that if he was in security intelligence he wouldn’t be able to say so. Harris tells her how he had selected his old friend, the late James Le Mesurier, for the assignment that would set up the White Helmets; and Harris had previously recounted how he had set out with another good friend, William Wiley, to train and support the Syrian investigators to be used by CIJA. These two initiatives were created under the auspices of Harris’s company ARK, funded by UK and other Western states. Since the early days of unrest in Syria, Harris has overseen the creation of ‘stabilisation’ operations in Syria on behalf of the British government, in alignment with the US and other Western states.

So the creation of both CIJA and White Helmets originated from strategic thinking, evidently broadly agreed by US and UK governments, on how to manage the anticipated transition in Syria to governance by a more compliant regime.

The projects overseen by Harris and his counterparts were premised on the prospect of rule by the Syrian government being supplanted by alternative arrangements that the British and allies meanwhile already aspired to help develop in areas under opposition control. The overall strategy evidently envisaged – going by the statements of aspiration and reports of achievements relayed in tender documents to UK FCO that have been leaked – a benign set of civil arrangements being set in place for the benefit of a welcoming civil society with order preserved by UK and US funded police and security being supplied by a Moderate Armed Opposition (MAO). In this vision, disciplined moderate forces would be protecting what UK referred to as liberated areas against both government forces and sectarian extremists, including ISIS. The leaked documents show that UK Government commissioned strategic communications companies to reinforce in their own public’s mind this idea of a flourishing MAO that UK itself provided only non-lethal aid to.

But facts on the ground were recalcitrant. As was learned early on by those who do not rely on mainstream press for information, the notion of a MAO quite quickly proved largely illusory, and yet UK nonetheless paid strategic communications contractors to burnish the myth (Cobain et al 2016; Curtis 2020).[2] (Among the contractors providing media support for the MAO was InCoStrat, a company co-founded by Emma Le Mesurier, who later became ‘Chief Impact Officer’ for Mayday and whose perspective has some centrality to the Mayday podcasts that give tribute to her late husband.)

It is these circumstances, less ideal than their project descriptions were premised on, that Mayday and CIJA have had to reckon with on the ground. The White Helmets were constrained by the warlords of the zones they operated in (Beeley 2018), and these included members of terrorist organisations. For CIJA’s Syrian investigators, the Free Syrian Army (FSA) was an important “partner” since they ‘operate mostly out of FSA-controlled areas and rely on the rebel fighters for physical security, logistical support, and access to prisoners and captured documents.’ (OCHA 2012) Yet the FSA itself has been described as a ‘largely criminal enterprise’ (Business Insider 2013) and one of the investigators admitted to The Guardian that a local commander of (designated terrorist organisation) al Nusra covertly provided the assistance of his fighters (Borger 2015). So evidence against the FSA is unlikely to have been gathered by CIJA, and the question whether CIJA could have been receiving witness testimony from captives and kidnap victims, who may have been tortured or murdered, is a further troubling one.

So there was something of a disconnect between the rhetoric of ‘stabilization’ in the service of ‘transitional justice’ and the reality of what Harris’s organisations could actually achieve on the ground.

But if fulfilment of the primary stated purpose of the White Helmets was not easy to assure, its public relations role has been a phenomenal success – with universally glowing tributes in the Western media and entertainment worlds. It hasn’t required hard evidence, duly tested, to construct and maintain this reputation (and Mike King’s efforts to track down evidence from the White Helmets for their claims have so far been rather forlorn). As for CIJA, its reputation depends, by contrast, on its promise of producing hard evidence; and since to date this has not been duly tested, the public relations campaign has had to focus on creating faith in the promise. This has to a significant degree been achieved, and yet faith in an as yet unfulfilled promise is perhaps more vulnerable to being shaken than is faith in men depicted carrying babies from danger to safety.

So if faith in the White Helmets nevertheless comes to be undermined, it can be anticipated that faith in CIJA might then be harder to sustain, at least in the court of public opinion (and, in consequence, in the calculation of funders too).

But the issues for the present discussion have an importance that transcends questions about particular organisations like CIJA. The focus now is to be not on how far reality is from what was presupposed in planning Syria stabilisation operations and the accompanying strategic communications programme, but in the ideal vision of the mission itself.[3]

UK’s misbegotten doctrine of ‘transitional justice’ in Syria

Accountability is part of what justice consists in, but, as noted at the start of this article, it is only a part; furthermore, justice itself is only part of what people seek in dealing with a conflict situation. Something they seek no less, and in many cases likely more, is peace. It is arguable that more determined efforts at peace and reconciliation might have been very much better than the retributive justice that can only be sought after the harm has been done.

This line of thought was commented on by Alistair Harris in a co-authored paper for RUSI in 2013, ahead of the round of tenders referred to above: ‘The pressing need is peace and security and arguably this must come first and precipitate a process of state building through the re-establishment of the rule of law. However, considering that the conflict in Syria is unlikely to end anytime soon, it would be irresponsible to wait any longer.’ Yet there appears to be a disconnect in this argument between the aspiration and the reality on the ground as described in the paper:

‘There are real debates going on within Syria as to what law to apply, be it the Syrian civil code, Shariah law, or the Shariah-inspired Unified Arab Criminal Code. But what is clear is that without support to Syrian legal professionals within Syria then it will be Al-Haya’a Al-Shar’iya, the judicial arm of the extremist group Jabhat al-Nusra, that will seek to lead in the provision of justice.’

The question this reader finds perplexing is, if groups like al-Nusra are in a position on the ground to impose their chosen brand of justice over a territory, how simply training legal professionals in an alternative legal code would alter that position. For that would seem to depend on there being genuinely moderate forces in charge on the ground.

Another puzzling claim in the paper – given that it is ostensibly about supporting law and order on the ground – is that ‘The judges and prosecutors need training in international humanitarian law.’ There is no reason explicitly stated in the paper to explain this need. The implicit connection is the notion of ‘accountability’, but this is doing a lot of work in trying to connect a concern for Syrians on the ground with aims of international prosecutors.[4]

Given this, it is significant to note that one of the paper’s co-authors is Toby Cadman,[5] a co-founder of Guernica 37 International Justice Chambers, who has been spearheading the push for Syrian war crimes prosecutions in Europe under ‘universal jurisdiction’. The other co-author is Mouaz Moustafa, who headed the US-backed Syrian Emergency Task Force. He liaised with Qatar to bring to the West the individual codenamed Caesar and photos of emaciated and tortured bodies said to have been from Syrian detention facilities. These photos provide, according to Stephen Rapp – who was formerly President Obama’s Ambassador-at-Large for War Crimes Issues, and brought American support to CIJA, becoming also a CIJA commissioner – ‘much better evidence than has been available to prosecutors anywhere since Nuremberg’. While this is a contested claim,[6] the reference indicates the ambition of those pressing for ‘accountability’ of the Syrian leadership. (Incidentally, Rapp and Moustafa had previously lobbied for regime change in Libya.)

So an impression forms that the focus of justice as accountability has been more about legitimating the anticipated regime change in Syria than in ameliorating conditions on the ground for ordinary civilians living under the armed groups that Britain and allies want the public to believe support civil life.

But there is a more significant exclusion from attention that comes about by emphasising the unique culpability of Syrian government. Whatever war crimes may have been committed in its name, there would not have been the occasion for these to occur were it not for the creation of a state of war in Syria in the first place.

It is therefore salient to reflect on the fact that back in October 2011, the UN Security Council could have heeded the appeal of the Syrian government for assistance, as would have been in accordance with the second pillar of the Responsibility to Protect. Instead, US, UK, France and their allies chose confrontation – emphasising that the Syrian government should be held wholly accountable for the violence that was unfolding. The Russian proposal of supporting dialogue and conciliation in Syria was dismissed by Western states as politically motivated, but it reflected the view of the other BRICS countries too and stands up to scrutiny today, in my view, better than the speeches of its opponents. It included a warning that the reason for the growing violence in Syria ‘was not only rooted in the hard actions of Syrian authorities. The “radical” opposition had not hidden its extremist bent, hoping for foreign sponsors and acting outside the law. Armed groups … were taking over the land, killing people who complied with law enforcement.’

We now know that the West did engage covertly in intervention, just as Russia foresaw. According to Mark Curtis (2020), ‘Evidence suggests that Britain began covert operations in Syria in late 2011 or early 2012. The UK was intimately involved in arms shipments, training and organising the opposition in a years-long secret operation with its US and Saudi allies.’ Britain became involved in the “rat line” of weapons delivered from Libya to Syria via southern Turkey reported by Seymour Hersh (2014). Britain was intimately involved in the CIA’s billion dollar ‘Timber Sycamore’ programme’, writes Mark Curtis (2018).[7] In short, Curtis states: ‘UK policy has helped to prolong and radicalise Syria’s devastating war’.

In these circumstances, for the US, UK and allies to then press a wholly one-sided accountability agenda is morally bankrupt. The policy underpinning it could be regarded as criminally cynical: it placed the West’s goal of regime change in Syria above the interests, and the very lives, of the Syrian people, without the slightest regard for anyone’s human rights. Instead of seeking to reduce the suffering of people in Syria, they fuelled it.

Finally, it has not only been covert acts of war that Western nations have undertaken against Syria. They can also be accused of committing a particular act of war that constitutes a crime against peace. On 14 April 2018, US, UK and France launched 103 missiles against Syria. The pretext for this was the alleged chemical weapons attack, a week earlier, on Douma.

On the same day as the West’s missile attack, The Times newspaper’s earliest edition – prepared shortly before the raid started – featured on its front page a verbal attack on members of the Working Group, defaming us as ‘Apologists for Assad’.

This was due to our scepticism about the truth of chemical weapons allegations – scepticism shared even at the time by some of Britain’s most senior military figures who used the freedom of speech afforded by retirement from active service to voice it.

Now, three years later, the Working Group’s analysis of the Douma event stands unrebutted. The concern we voiced then is now being articulated by an increasing number of eminent figures around the world. A recent Statement of Concern has been signed by people who have dedicated their lives to serving and building institutions that uphold international justice. The specific concern of that Statement – which many fear could be emblematic of a much wider comparable cause for concern – is that a false report of events has been published by the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) under political pressure from the states that themselves stand accused of committing the war crime of unlawfully bombing Syria.

This is what CIJA’s Nerma Jelacic was referring to when she spoke of the Working Group’s revelations of the OPCW’s ‘tainted evidence’. Chloe Hadjimatheou’s Mayday podcasts have purported to address the concerns about the Working Group’s analysis, but they have simply generated further questions that she, and all her colleagues who attempt to shore up a discredited narrative on Syria, have been unwilling – because unable – to answer.

Conclusion

What the lurid story of the sting that occasioned Paul McKeigue’s lapse of judgement opens us out onto is a much more serious reason why so many people have gone to so much trouble to denigrate members of the Working Group.

They cannot combat the truth. They can only try and exploit the human weaknesses of seekers after it. But that is not a sustainable strategy, because truth is available for all to see and doesn’t depend on any particular individuals or groups.

Viewed in this light, CIJA’s self-defeating sting operation merely exhibits how the remnants of a failed and morally bankrupt foreign policy venture are disintegrating. The policy has left in its wake such devastation and suffering caused to the Syrian people that all complicit in it share moral responsibility for a terrible crime against humanity.

Endnotes

[1] Examples include:

Al Jazeera documentary Syria Witnesses for the Prosecution

Channel 4 documentary Syria’s Disappeared: The Case against Assad

Julian Borger, ‘Syria’s Truth Smugglers’, The Guardian, 12 May 2015

Ben Taub, ‘The Assad Files’, The New Yorker, 18 April 2016

[2] ‘The UK’s propaganda effort for the Syrian armed opposition began after the government failed to persuade parliament to support military action against the Assad regime. In autumn 2013, the UK embarked on behind-the-scenes work to influence the course of the war by shaping perceptions of opposition fighters.’ (Cobain et al 2016) The UK hubristically imagined it could ‘help mould a Syrian sense of national identity that will reject both the Assad regime and Isis.’

‘Contractors hired by the Foreign Office but overseen by the Ministry of Defence (MoD) produce videos, photos, military reports, radio broadcasts, print products and social media posts branded with the logos of fighting groups, and effectively run a press office for opposition fighters.’

From Mark Curtis (2020):

‘The projects were run by Britain’s Ministry of Defence (MOD) and military intelligence officers and given the codename Operation Volute, although those involved in the work refer not to propaganda but to “strategic communications”.

They were guided by the government’s National Security Council, Britain’s highest policy-making body, with a budget worth £9.6-million during 2015-16 alone, with more money earmarked for later years.

The documents show that the UK was covertly running parts of the Syrian opposition. It awarded contracts to communications companies that selected and trained opposition spokespeople, managed their press offices and developed their social media accounts.

Although the propaganda initiative was primarily aimed at Syrians both inside and outside the country, the documents make clear that UK audiences could sometimes be “a specified target” of media material and that some “may reach the UK information space”.’

‘Documents on the UK’s propaganda campaign examined by the Guardian in 2016 list several groups considered to be part of the “moderate armed opposition”. One was Jaysh al-Islam, a coalition of some 50 Islamist factions operating in and around Damascus and funded largely by Saudi Arabia.’

‘The new revelations are remarkable in that they confirm the extent to which the publicity work of opposition groups that the UK government has consistently invoked as legitimate opponents of the Assad regime can be traced back to London itself.’

‘The level of media management is noteworthy. Some prominent British journalists visiting Istanbul would be introduced to Syrians acting as opposition spokespeople, who had been prepared for the encounter by British handlers.’

‘Britain’s role in the war in Syria has been distinctly under-reported and mis-reported in the UK mainstream media. While the media has widely reported on UK military operations against Islamic State, its covert operations against the Assad regime have received much less attention.

The media has been keen to repeat government lines about the atrocities committed by the Assad regime. By contrast, opposition forces have been largely given a free pass, with many reports failing to even note that in many parts of Syria, those groups have been controlled or dominated by jihadists.

‘Noteworthy also is that the propaganda element of these programmes was accompanied by an intelligence-gathering role, to acquire further information on the alliances and activities of opposition forces. A key benefit was assessed to be the British government’s “connectivity to different (armed or non-armed) networks”.’

From Mark Curtis (2018):

‘Jaish al-Islam (Army of Islam), a newly formed coalition of around 50 Islamist factions funded by Saudi Arabia, was one of the groups considered by Britain to be part of the “moderate armed opposition”.’

‘Peter Ford, the former British ambassador to Syria, told a parliamentary enquiry in 2016 that the existence of “moderate” groups among the armed opposition was “largely a figment of the imagination”.

Although the FSA contained some secular units, it was in effect allied to IS until the end of 2013 and was collaborating with it on the battlefield until 2014, despite tensions between the groups. “We have good relations with our brothers in the FSA,” IS leader Abu Atheer said in 2013, having bought arms from the FSA.

The UK-supported rebels had an even closer relationship with Nusra. The BBC’s Paul Wood reported in 2013 that “the FSA is so close to Nusra it has almost fused with it”. The FSA has collaborated regularly with Nusra throughout the conflict.’

‘In 2017, the British government revealed that it spent £199m ($277m) since 2015 supporting the “moderate opposition” opposed to Assad and IS.

This support included “communications, medical and logistics equipment” and training journalists to develop “an independent Syrian media”. But details of more recent UK covert operations remain murky, and few recent media reports have uncovered the UK role.’

[3] Even focusing on accountability only, “You can’t set the basis for a state based on rule of law when you basically absolve one side,” said Claudio Cordone, head of the Middle East and North Africa programme at ICTJ.’ https://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/analysis-beginnings-transitional-justice-syria

[4] Perhaps it is this the authors have in mind with their rather elusive mention of having ‘inadvertently stumbled upon a golden opportunity to address issues of justice, accountability, transition and reconciliation simultaneously.’

[5] I went to Wikipedia to check his affiliations, only to find that Toby Cadman does not have a Wikipedia entry. I reflected wistfully that this affords his reputation a protection – e.g. from references like this – that is unavailable to others of us! He should be in Wikipedia, given that he is involved in significant activities, including seeking to bring prosecution cases under the principle of universal jurisdiction in European courts. Apparently, in 2012 he had been engaged by UK FCO ‘to head a team to investigate crimes committed in the Syrian Arab Republic.’

As regards the CIJA sting, I note that he tweeted: ‘The authorities will need to look into this carefully and scrutinise the role of the working group members’ and he referred to a ‘disinformation campaign’. Everyone should be aware that there was no plurality of members involved in the sting and that accusations of disinformation require to be proved.

[6] As I noted in an earlier article, the Caesar photos have been more actively promoted on the American side than the British. So Mohammad Al Abdallah, Executive Director at the US-funded Syria Justice and Accountability Centre – which Harris had had a hand in setting up – and is a conduit of US funding to CIJA, claims that it was Caesar photos that at that time had influenced cases in Germany and Spain, rather than the documents. But Wiley qualifies that claim: ‘‘In and of itself, would it make a case against Assad? No, not at all, not at all.’ Harris explains, ‘The Caesar photos are valuable as they show the scale of the atrocities, but … not the chain of command through which this was orchestrated.’ Nor, I have elsewhere suggested, do they even sufficiently establish which side was responsible for those atrocities. Wiley sees the value of the Caesar evidence as emotive: ‘It puts a human face on the documentation, on the charges. It’s a dead human face but it’s a human face.’ (There are in fact significant uncertainties about the photos’ evidentiary value, as I discuss elsewhere.)

[7] Mark Curtis (2018) expands on this:

‘UK covert operations appear to have begun in late 2011, a few months after popular demonstrations started challenging the Syrian regime in March of that year. … The UK and its allies spotted an opportunity, which they had long been looking for, to remove an independent, nationalist regime in the region and deepen their overall control of the Middle East.’

‘Qatar began shipping arms to opposition groups in Syria with US approval in spring 2011, and within weeks, the Obama administration was receiving reports that they were going to militant groups. By November, former CIA officer Philip Giraldi wrote that “unmarked NATO warplanes” were arriving in Turkey, delivering weapons and 600 fighters from Libya in support of the Free Syrian Army (FSA), a group of Syrian army deserters.’

‘Britain’s MI6 and French special forces were reportedly assisting the Syrian fighters and assessing their training, weapons and communications needs while the CIA provided communications equipment and intelligence.’

‘Britain became involved in the “rat line” of weapons delivered from Libya to Syria via southern Turkey, which was authorised in early 2012 following a secret agreement between the US and Turkey. Revealed by journalist Seymour Hersh, the project was funded by Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Qatar while “the CIA, with the support of MI6, was responsible for getting arms from Gaddafi’s arsenals into Syria”.

The operation was not disclosed to US congressional intelligence committees as required by US law, and “the involvement of MI6 enabled the CIA to evade the law by classifying the mission as a liaison operation”.’

‘The Telegraph reported on a Middle Eastern diplomat saying that Qatar is responsible for Nusra “having money and weapons and everything they need”.’

Reblogged this on THE ONENESS of HUMANITY and commented:

The good innocent people of Syria have suffered near ten years of brutal, immensely painful, covert state-sponsored terrorism and criminal violence – forced upon them by powers outside the country. Any human being on Earth with an ounce of morality remaining in their possession will agree that the Syrian people’s immensely tragic suffering must now – finally – come to its total end…

Pingback: The CIJA (BBC) sting operation from perspective of international law | The Wall Will Fall

The Times newspaper’s earliest edition – prepared shortly before the raid started – featured on its front page a verbal attack on members of the Working Group, defaming us as ‘Apologists for Assad’.

========

Point out to them, The Times, that they are apologists for war criminal/terrorist usa, uk, canada, … .

Pingback: Media Coverage of OPCW Whistleblower Revelations | Tim Hayward

Pingback: NRK podcast “Hvorfor går IS fri»? | steigan.no